Manchester United’s Transition-Ball: A Visionary Approach Or a Tactical Disaster?

Eric ten Hag, during Manchester United’s pre-season tour in the United States, declared, ‘We want to be the best transition team in the world.‘ The Dutchman has set his sights on transforming the team into a dynamic, quick, and aggressive unit, aligning this vision with the ‘United Way.’ Yet, seven months into the 2023-24 season, the Red Devils find themselves more often on the back foot during transitions rather than using them to their advantage.

After 14 wins, two draws, and 10 losses in 26 league matches, Manchester United find themselves in a tough battle for a top-four spot after they bowed out of the Champions League group stage and were eliminated in the EFL Cup’s fourth round.

This begs the question: What’s holding back ten Hag’s transitional strategy? More importantly, even if it starts to click, is it a sustainable approach that can propel Manchester United back to competing for the League title season after season?

What Is Transitional Football?

Before diving into the specifics of Manchester United’s situation, let’s clarify what we mean by transitional football.

A “transition” occurs when possession shifts from one team to the other. During this shift, the team that loses the ball often finds itself disorganized, creating opportunities for the opposing team to exploit any available spaces.

While some may associate transition-focused football with a strategy of sitting back in a deep defensive formation, inviting pressure, and then capitalizing on counter-attacks, this perception is outdated. Today’s transitional teams aim to regain possession as close to their opponent’s goal as possible.

Rather than adopting a deep defensive stance, these teams prefer a high defensive line that compresses the playing field. This strategy involves midfielders and forwards acting as the initial line of defence, exerting aggressive pressure to quickly win back the ball.

Pressing naturally leads to the concept of counter-pressing, or “Gegenpressing,” a tactic refined by Ralf Rangnick and brought into the spotlight by Jurgen Klopp during his tenure at Borussia Dortmund and Liverpool.

Counter-pressing involves the immediate application of pressure upon losing possession, with the goal of recovering the ball as quickly and as close to the opponent’s goal as possible. This strategy grants the pressing team a significant advantage, often catching their opponents off-guard and taking advantage of their disarray during these transitional moments.

This circles us back to ten Hag’s vision for Manchester United. If the Dutchman aspires for his team to be the best transitional force globally, it stands to reason that they must also excel in pressing, correct?

Manchester United’s Pressing: A Blessing or a Curse?

Neither the stats nor the eye test suggest that United’s pressing game is top-notch, not by Premier League standards, and certainly not globally!

So, let’s look at the statistics first. According to Opta Analyst, United allows around 12.2 passes before they make a defensive action (PPDA), which puts them ninth in the league. This might hint that United’s press isn’t as intense as some teams like Liverpool or Spurs, but they’re still doing better than many others.

When creating high turnovers, Ten Hag’s team is eighth in the league with 231. So, in addition to not being intense, United’s pressing is also not efficient. For example, even Everton, who press less aggressively than United with a 14.0 PPDA, ranks third in turnovers with 250.

Saying United’s pressing doesn’t exist might be harsh, but is it too harsh?

This season, teams playing against United have managed to complete 81.48% of their build-up passes successfully. To put that into perspective, teams facing Luton Town have a success rate of 80.43%. So teams actually find it easy to play through United’s press.

This drop in pressing efficiency could be due to a few reasons, like players not timing their runs well or not positioning themselves properly to block passing lanes. But there’s a bigger issue at play here, one that’s not just making United’s press less effective, but also contributing to their defensive troubles.

A Gulf Between the Lines

As we discussed earlier, the whole point of aggressive pressing is to win back possession as close to the opponent’s goal as possible. To do this effectively, you need the entire team to push up: one, to compress the playing area, making it tougher for the opposition to find space; and two, to maintain a tight formation, minimising the space opponents have to play in and reducing the distance your players need to cover when pressing.

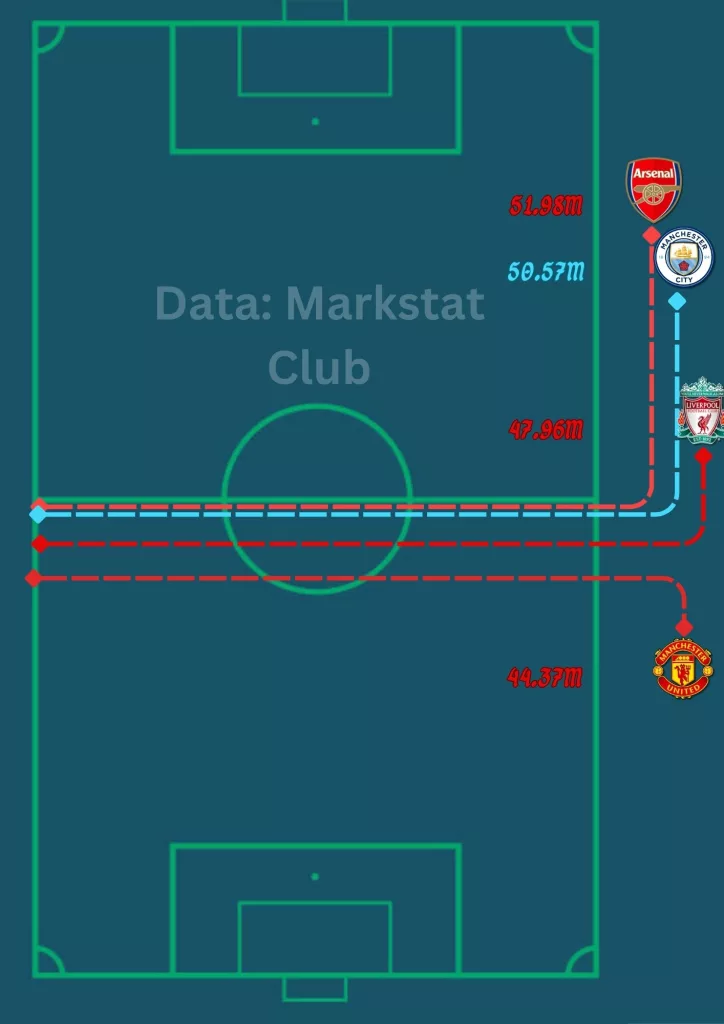

Take this season’s examples: Arsenal, City, and Liverpool have set up the highest defensive lines in the league. Liverpool, under Klopp, ranks third, with their defensive line averaging a height of 47.95 metres. United, contrastingly, are positioned 13th for the height of their defensive line, at 44.37 meters—this places them even below Burnley and Everton, who are opting for more advanced defensive positions.

Combining a lower defensive line with a press that’s more intense than average creates big gaps in midfield, which opponents can exploit. This is precisely what’s been happening to Manchester United this season, from their opening win against Wolverhampton to their recent loss to Fulham at Old Trafford. Let’s look at specific moments from both matches.

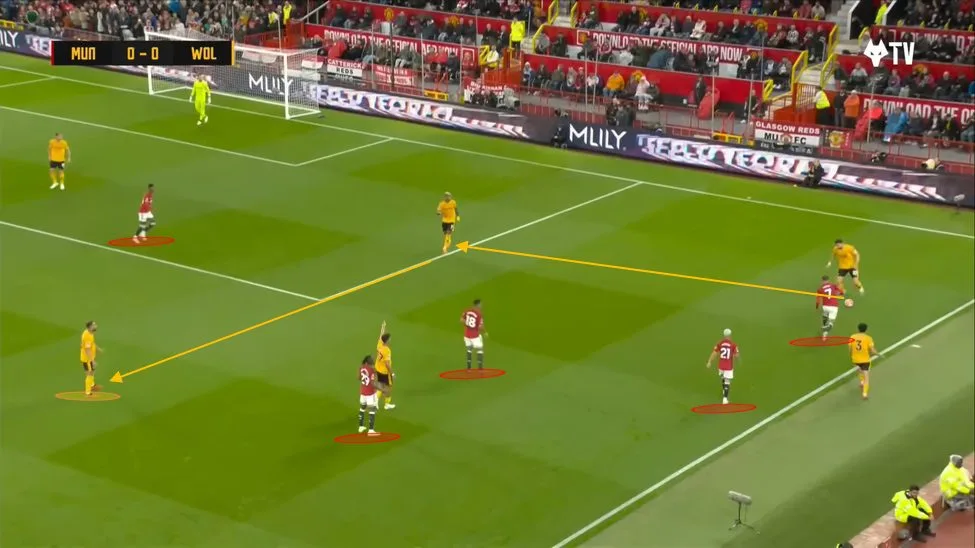

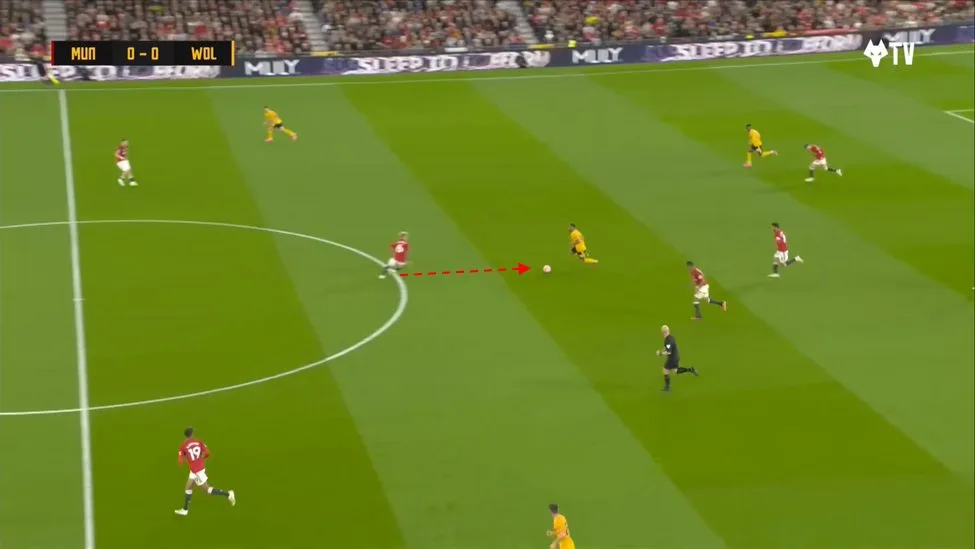

In one instance against Wolves, Mason Mount lost the ball in Wolves’ defensive third, triggering a counter-press by United. Seven United players joined the press (Bruno and Garnacho are yet to appear in the frame). However, with Cunha dropping back, Wolves managed to find an extra player, bypassing United’s press.

After shaking off Casemiro, the Wolves’ forward also succeeded in driving past Lisandro Martinez, moving the ball further up the pitch. This moment, they highlighted a significant issue: the disconnect between United’s pressing efforts and their defensive line, especially noticeable once Cunha took control of the ball.

Lisandro Martinez, renowned for his proactive defending approach, attempted to close down the space effectively. However, Cunha succeeded in manoeuvring past him, creating a precarious situation for United as Wolves advanced with the ball.

Lisandro Martinez stands out as United’s quickest and most assertive defender. However, injuries have limited him to just eight league appearances this season. This has left ten Hag to rely on Rafael Varane, Harry Maguire, Victor Lindelof, and Johnny Evans—defenders who aren’t ideally suited for a high defensive line. Could this be a factor in the Dutchman’s preference for a lower defensive stance?

Reflecting on United’s defensive woes, particularly their tendency to defend in disjointed blocks and the resultant large gaps in midfield, let’s delve into some key moments from their latest loss—their 10th in the league and 15th across all competitions.

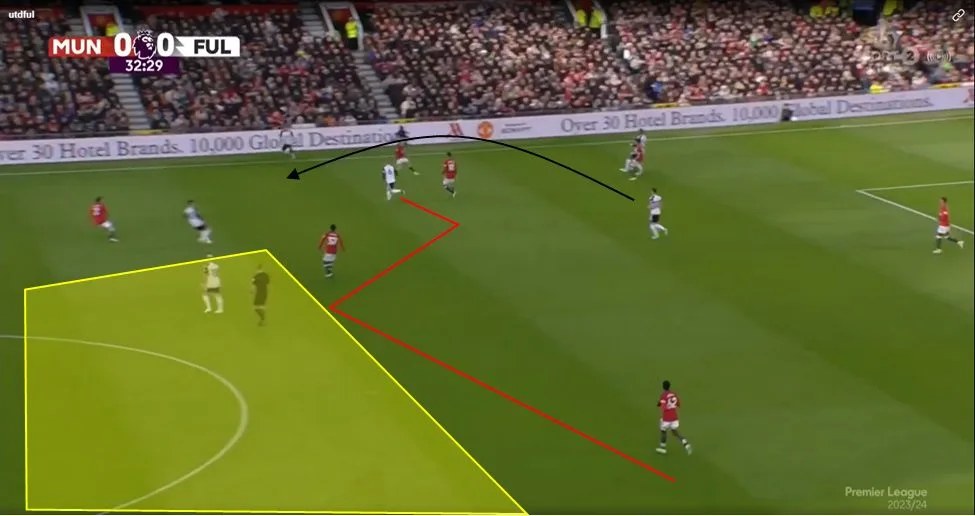

In this match, Fulham managed to bypass United’s press with a lofted pass to their fullback, a reoccurring issue the Red Devils had this season. This tactic has led to a number of goals conceded from cutbacks, further exacerbating their defensive vulnerabilities.

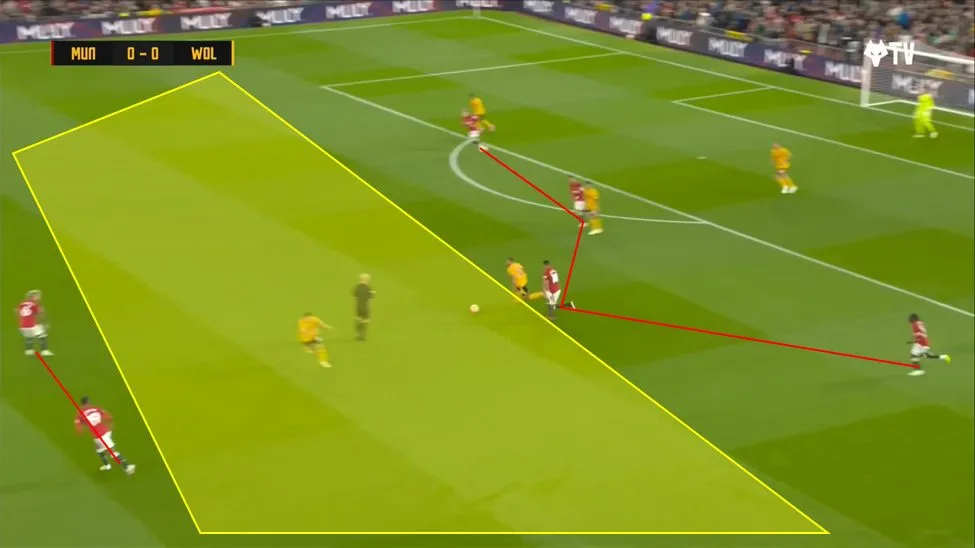

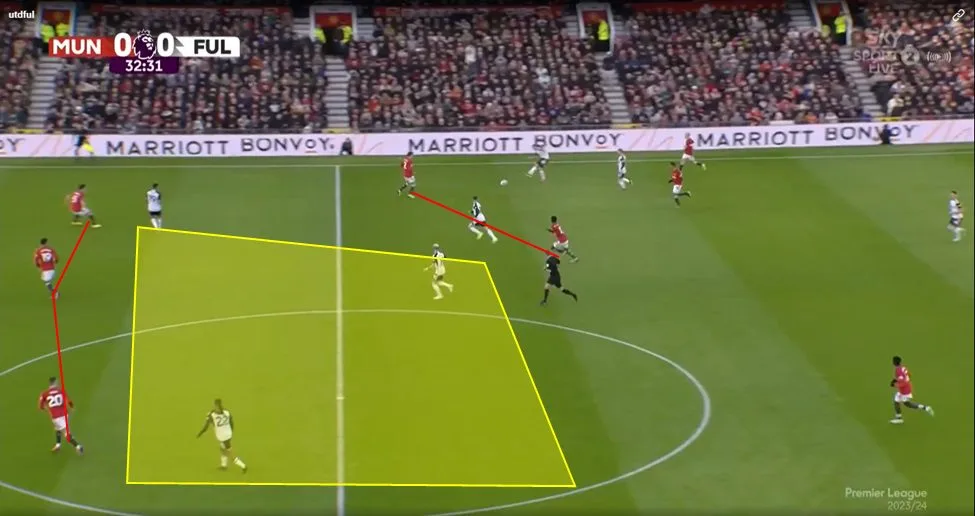

Notice again the clear disconnect between United’s pressing and their defensive line, resulting in a vast gap in midfield. This gap made it exceedingly difficult for United’s players to cover the space effectively.

This scenario has become all too familiar for Manchester United. Rather than engineering transitional opportunities through their pressing, their pressing structure is ironically setting up transitional chances for their opponents. Only Sheffield United had allowed more shots in the Premier League after the game against Fulham. Moreover, they possess the third-highest expected goals against statistics, standing at 1.69 xGA. These statistics underscore United’s defensive difficulties, which can largely be traced back to their disjointed pressing approach.

Baiting the press or playing over it?

Moving away from pressing, another method of making the best of transitional football involves focusing on the build-up phase—circulating the ball within your own defensive third to draw the opponent’s press and thereby creating spaces behind for your players to exploit. This approach is reminiscent of the strategies employed by Roberto De Zerbi or Xabi Alonso with their respective teams.

To successfully implement this strategy, a team needs defenders who are technically proficient and a goalkeeper who is comfortable with the ball at his feet. For United, Lisandro Martinez stands out as their most technically skilled defender, but he has, unfortunately, spent the majority of the season sidelined due to injuries. Regarding the goalkeeper, Manchester United invested €51 million to acquire Andre Onana from Inter Milan, securing a keeper renowned for his footwork. Yet, with Lisandro’s absence and the other center-backs average ball-handling skills, ten Hag has opted for a strategy that bypasses rather than baits the press. United have shifted to playing “over” the press.

Onana’s ball-playing skills have obviously been limited to going long. He is now the seventh keeper in the league for most attempted long passes, with 319. The first sign that Ten Hag’s build-up phase is not what you’d expect.

While a transitional style naturally emphasises directness and moving the ball quickly to the attacking third, United might be taking this too literally. According to Opta Analyst, the Red Devils rank second in the league behind Liverpool for the most direct attacks with 66 but fall to ninth for build-up attacks, tallying 64. This over-reliance on direct play is reflected in their playing style; they’ve managed only 264 open play sequences of 10+ passes. In comparison, Liverpool, known as the epitome of direct football, has compiled 418 such sequences.

Not only does United aim to complete sequences in fewer passes, but they also execute these sequences at a blistering pace, averaging just 9.99 seconds per sequence. For such a fast and direct style to be effective, a team needs technically skilled players—those capable of delivering a perfectly timed pass to a teammate’s preferred foot and individuals who can change the dynamics of the game with a single touch. But does United possess these types of players?

The statistics suggest otherwise. United leads the league in passes that have resulted in offsides, with 67 instances, indicating less than ideal timing. Furthermore, they rank fifth for having the most passes blocked by an opponent intercepting the ball’s path, pointing to a lack of precision among United’s players.

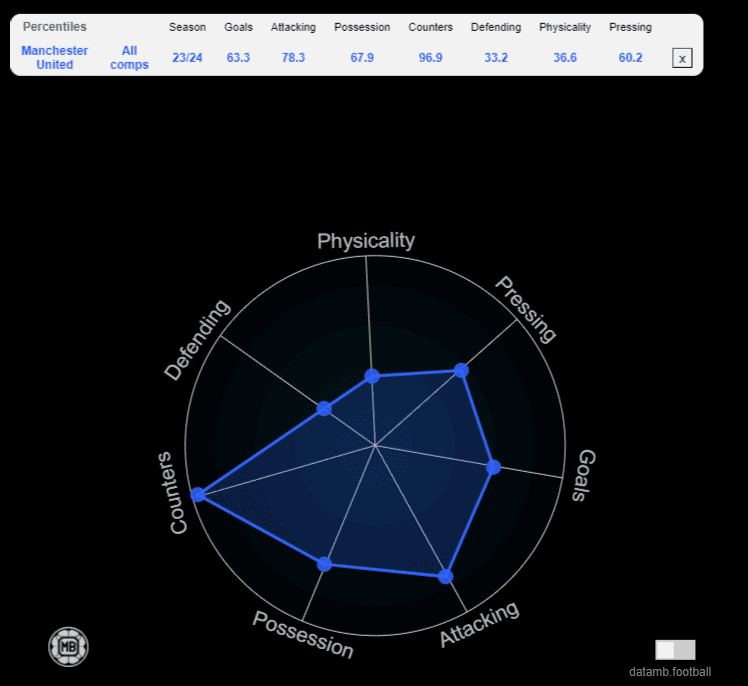

The efficiency of United’s supposed build-up play is also not up to par, with an average success rate of 82.87%, placing them ninth in the league. This radar graph by Data Mb encapsulates our discussion, visually representing the areas where United’s approach falls short.

A Sustainable Style or One to Ditch?

Manchester United’s pressing and build-up phases fall short of the standards required to become the world’s best transitional team. Instead, Erik ten Hag seems to have doubled down on an end-to-end style of play that leans heavily on counter-attacks. It’s worth noting that Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool initially displayed a similar level of chaos, embracing an aggressive, front-footed approach. Yet, over time, Liverpool refined their possession game, gradually moving away from chaos towards a more controlled style of play while keeping that essence of directness through their “Gegenpress”.

Unfortunately for United fans, the strategy that ten Hag has branded as the “United Way” bears a striking resemblance to the approach Ole Gunnar Solskjaer previously implemented at the club. This strategy, which relies on counter-attacks while incorporating a semblance of pressing, appears to be doing more harm than good.

Even if INEOS decides to back ten Hag for a full season under their ownership, the Dutchman must reevaluate his tactical approach. Beyond the disjointed structure, poor performances, and lacklustre results, one glaring issue rendering ten Hag’s style unsustainable is its intensity and the physical toll it takes on players. The club has seen 17 of its players sidelined with various injuries, most of them muscular, with Rasmus Hojlund being the latest addition to the injury list.

Erik ten Hag’s goal to turn Manchester United into the best transitional team is understandable, given the success teams like Liverpool have seen in recent years. However, the way he’s going about it is causing problems. It’s not fitting well with what the players can do or what the fans want. To make it even worse, this intense approach is causing more injuries to players, something that might affect the squad in the future.