Fan Cams and the Voiceless Victims of Rage

In the realms of performance, the quest for authenticity remains ever-present. The two-time Oscar winner Spencer Tracy offering advice to a young Katharine Houghton distilled the essence of a successful performance down to one sentence: “Know your lines, and don’t bump into the furniture.” She had, I presume, hoped to replicate a career like that of her aunt: the mercurial Katherine Hepburn. However, unaware of the new breed of performers migrating from the east coast of the United States, her career never quite lived up to that of Hepburn.

Following her role between Tracy, Poitier, and Hepburn in Look Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), Houghton’s career drifted away from stardom. Meanwhile, the likes of Marlon Brando and Al Pacino completed their migration from New York to the Oscars. ‘Method’ actors by trade, these actors represented a revolutionary style born in Moscow and brought a new level of authenticity to the silver screen that audiences adored. For these actors, as Claudia Ruth Pierpont notes: “…the goal was a paradox: real emotion, produced on cue”. In performance, nothing that was rewarded ever goes unduplicated. The ‘Method’ soon became the only method.

The Rise of Fan Cams

The seemingly disparate worlds of Stanislavsky and Football’s Fan Cam culture converge on a fundamental principle: the pursuit of real emotions. As actors strive to immerse themselves in their characters, blurring the lines between performance and reality, fan cam creators aim to capture and convey genuine reactions, fueling a captivating cycle of expression and consumption.

These fan-driven videos, capturing moments of elation or despair in the aftermath of games, have skyrocketed in prominence, drawing viewers in with their raw emotions and compelling narratives. Fan channels following Arsenal FC (AFTV) and Manchester United (The United Stand) remain particularly popular, boasting over 1.5 million subscribers each.

Addressing the Oxford Union in 2022, AFTV creator Robbie Lyle defined his venture as a deliberate departure from the hegemonised punditry pervasive in British broadcasting. Drawing parallels with the method actors of yesteryears, Lyle articulated a growing disillusionment with the sanitised and unrepresentative voices dominating the screens.

His venture would be a successful one – and not just for himself. Having found fame as regular contributors to the channel, AFTV has served to launch careers and given a voice to several people who otherwise wouldn’t have found one.

The Importance of Emotional Expression

In an emotional tribute to Lyle, Claude Callegari, a fiery stalwart of the channel, said: “…This guy gave me a chance to speak [when] no one else would.” A man who had struggled with his mental health and loneliness in anonymity found a purpose and a community in following his team. The period before Claude’s passing represents a timely reminder of football’s importance in the collective mental health of its followers.

Serving as a testament to their success and the rule of replication, online spaces for football have seen an explosion in new ventures, with youtube channels, blogs, and podcasts contributing to the democratisation of sports coverage.

A Safe Space

Before abandoning my predestined gender, I grew up in a council house in Manchester as the youngest of five boys. I know more than most that to ignore the importance of football to men in particular, or to police the emotional nature of its followers, is to discount a sobering reality men face today: that, without football, they would have very few emotional outlets, if any.

The only time I’ve seen men cry is through football. Watching England bow out to Portugal in the 2006 World Cup Quarter Final was perhaps the first time I realised, among some men, it’s okay to cry, at least as long as it’s about football. We’d cry tears of joy two years later when Manchester United were crowned champions of Europe in 2008, despite our reservations, a momentary peace from gender’s shackles.

Sport is a safe space for men to defy what society often trivialises or punishes. As Papyrus UK (A men’s mental health and suicide prevention charity) states on their website’s landing page: “Without having safe spaces that encourage opening up around others, most men have an ingrained notion that they should ‘man up’ by emotionally isolating and internalising their feelings.”

Perhaps the tears following John Terry’s fateful slip in 2008 were laced with a little more than simply football. Perhaps at that moment, it wasn’t “just a game.” For this reason, we should be sceptical before policing anybody’s emotions in response to a football match.

The Reinforcement of Rage

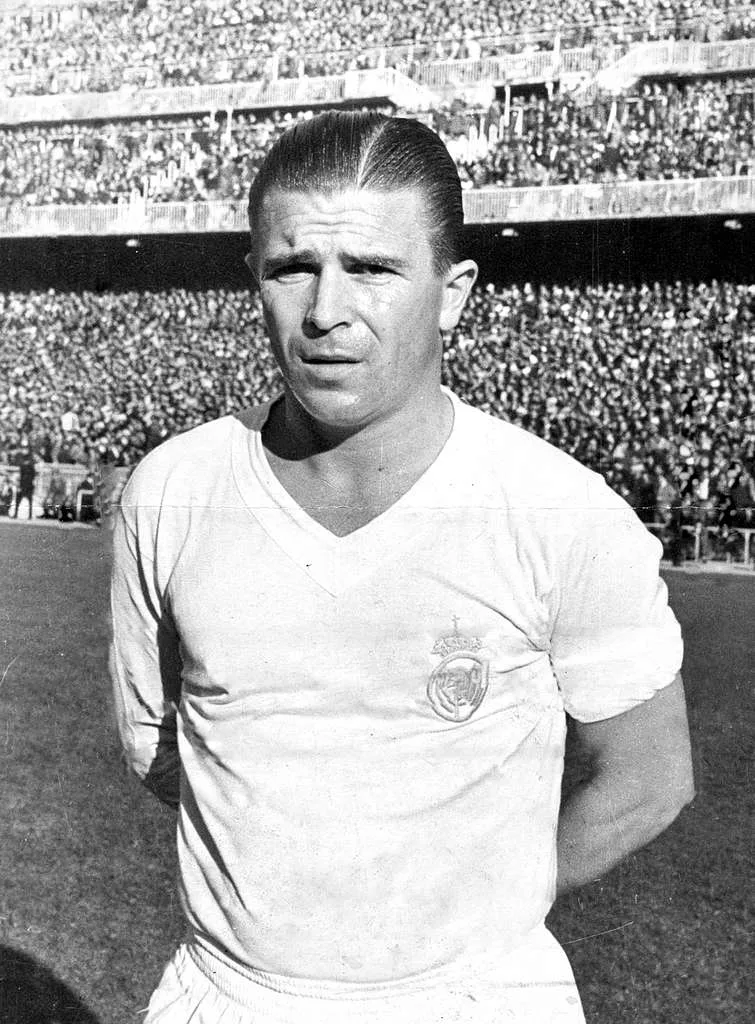

Remember the rule of replication in performance? Anything rewarded is replicated. Be it Johan Cruyff’s iconic turn in the 1974 World Cup against Sweden or Johan Cruyff’s footballing principles, success breeds emulation and imitation.

In the acting world, success means fame and awards. And whilst the method actors of the 1960s and ’70s boast several cabinets full of awards, cinephile readers are perhaps now aware of the dangers of method acting.

Be it Christian Bale’s frankly concerning weight loss for The Machinist (2004) or the mental toil of Heath Ledger’s pursuit to capture the essence of the Joker for 2008’s The Dark Knight, it’s apparent now that the practice has been relegated, marginally, to the more maverick actors on screen.

This becomes noteworthy when we consider what success means for fan content online. Clicks drive success in the world of online content. Glancing at the most popular fan channels on Youtube, it’s clear what generates attention. Any popular tab on these channels seems to be filled in large part with “rages,” “rants,” and “heated debates,” garnering views in the millions.

Reward

With clicks comes the reward of revenue. The few individuals who have found prominence in this economy of clicks seem to fall into two categories: the professional tantrum throwers and the click baiters. Perhaps a contentious categorisation, but it seems concerning that success in the sphere often boils down to toxicity outside of the Football’s smaller content creators.

AFTV stalwart ‘DT’ falling into the former category has generated a sizeable platform following from his contribution to the fan channel, whilst his compatriot ‘Troopz’ now throws tantrums for American outlet Barstool Sports. Mark Goldbridge of The United Stand, and clickbait master, boasts monthly viewers in hundreds of thousands, where he seems to revel in the contentious world of fan opinion by seemingly boasting about being blocked on social media by his Man United players.

It’s no wonder that fan cams today often feel like auditions to be the next main character on the scene. With each disappointment comes a queue of new tantrum throwers competing to earn those notorious keywords and clicks.

The Spillover Effect

Fan cams by their very nature amplify rage and anger in their own community by rewarding their displays with attention and the potential of financial gain. If rage leads to success in this sphere, what’s the value of emotional maturity, nuanced discussion, or the ability to control your own behaviour?

A study conducted in 2014 by academics at Lancaster University examined the frequency of abuse reports made to the police force in the northwest of England during three FIFA World Cup Finals. The researchers discovered a notable 26% rise in abuse reports when the national team achieved a win or a draw. Additionally, the study found that the number of reports increased by a more substantial 38% following a loss by the team.

These conclusions are not unique. The landscape of studies into the relationship between football and abuse grows larger every year.

Following Manchester City’s opener against Arsenal on April 26th, 2023, AFTV alumni Troopz raged at the goal, only this time directing his frustration at his partner who had, out of shot, “walked into the room,” during a live stream. The outburst represented everything this economy of sensationalised content craves. It was soon clipped and shared around social media by some outlets titled with laughing emojis indicating to viewers how funny they should find it.

The posts would soon be deleted when the desire for attention and consumption met the reality of football’s relationship with abuse. Troopz didn’t just “know his lines and avoid the furniture;” it was “real emotion produced on cue.” Like the now notorious method actors of old, the performance had spilled into his personal life and relationships.

Emotional Contagion

There is, of course, a chicken and an egg scenario here. Do people who can’t control their emotions find a platform to throw tantrums which leads to their personal success or do those who see others’ tantrums garner attention, try to imitate the behaviour in order to find success themselves? Whichever scenario it is, and I suspect both are true, there remains the problem of ‘Emotional Contagion’.

Emotional contagion refers to the process by which emotions are transferred from one person to another through nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language.

Several studies have shown that emotional contagion can occur in response to displays of anger. For example, one study found that when participants watched a video of someone expressing anger, they were more likely to experience anger themselves as measured by changes in their heart rate and skin conductance (Hess & Fischer, 2013). Another study found that when participants observed an angry person, they tended to mimic the angry person’s facial expressions. This, in turn, increased their own anger (Dimberg, Thunberg, & Elmehed, 2000).

Correlation

Even if the effect is marginal, the correlation is still relevant. The reward, normalisation, and amplification of uncontrolled anger increase the net aggression of its viewer base, at least some of the time, for some of the viewers, thus increasing the likelihood of emotional and physical abuse committed by those viewers.

Even if such individuals could claim to be performing their emotions, there remains the issue that individuals may lose the ability to draw a clear distinction between performative and genuine emotion. A study by Wiltermuth and Heath (2009) found that individuals who were instructed to act angry during a negotiation task reported feeling angrier than individuals who were not instructed to act angry, suggesting the expression of anger can lead to the genuine expression of that emotion.

You owe it to yourself to not be hurt by football

It serves neither the individual themselves, nor the wider community as a whole, to normalise, reinforce, and reward harmful behaviour. As Samuel L. Jackson recently said regarding method acting: “You’re supposed to be able to give emotionally and not be harmed by it.”

People affected by anger following football games, if separated from the fan cam economy, might explore sports-based interventions to help them lessen their anger or stop their abusive tendencies. A study published in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence found that men who participated in a sports-based intervention program had significantly lower levels of physical and emotional abuse toward their partners compared to men in a control group.

Sports-based interventions typically involve structured programs that use sports activities. Team-building exercises and group discussions are provided to promote positive attitudes towards women and discover non-violent conflict resolution strategies. These interventions aim to challenge harmful gender stereotypes and promote gender equality.

Without the influence of greedy algorithms, pushing toxicity and rage, the beautiful game makes a huge difference in all of our lives. We are united by this thing we call Football, whether it is your emotional outlet, community or identity. To allow algorithms and egos to amplify our worst behaviours is to discount the best that football has to offer. A beautiful game where the losers always have tomorrow, and the winners always remember today.