Man-to-Man Marking: The Most Underrated System In Football?

Upon watching my Sunday League team play at the weekend from the comfort of the sideline, I couldn’t help but feel our zonal approach to the task at hand was one of the main reasons we were suffocated inside our own box for 85 out of the 90 minutes of a cup final. Tactics are not too ripe in the realms of Sunday football, but there’s a growing itch inside me that wishes they were.

Last week we played a team that loved diagonal balls, usually from their centre-back to an onrushing overlapping full-back, with a winger tucking inside to confuse our own full-back. It was clockwork, time and time again. Whenever they got a yard, they pinged it, and more often than not, they found the mark they were looking for. It was continual torture, and in truth, our failure to adapt cost us the game.

The Man Marking System:

When walking away from the pitch that day, I cast my mind back to the Gian Piero Gasperini man-marking system deployed against Liverpool. That complete system aimed to negate the qualities of a team that is deemed better than yours in a number of aspects and subject them to possible long balls forward. Once that long ball goes forward, the percentage chance of you winning the ball back goes up, and it’s your duel winners and aerial specialists against their chance creators and nippy wingers. Such is the way modern football has gone. In the past, with battering ram centre-forwards, there was a much lower likelihood of your centre-halves or defensive midfielders winning the ball back, but now, the game has evolved.

My way of thinking was that if we placed our wingers strictly on their overlapping full-backs for the entirety of the game, we would negate that offence, which was quite clearly the other teams outstanding quality. You then force them to play centrally, which, judging by the way they built up within the game, is not something they would have been comfortable with.

The man-marking system is superior to the hybrid press in a number of ways. Manchester United’s zonal system this season has been castrated time and time again due to a simple clip ball to the oppositions full-back, who is more often than not in acres of pure space. When you fail to actually man-mark every player on the pitch, you leave zones free to run into; especially if your midfielders are pressing high and your defence is not.

What the experts say:

I spoke to two men with huge tactical knowledge in the football Twitter sphere, in the shape of htomufc and Jack Fawcett, who both had similar views on how the man marking system works. hto described the system as a better fit to zonal due to the fact you can limit the opposition in certain actions through the man-to-man approach, but with zonal, you still allow them space to work in.

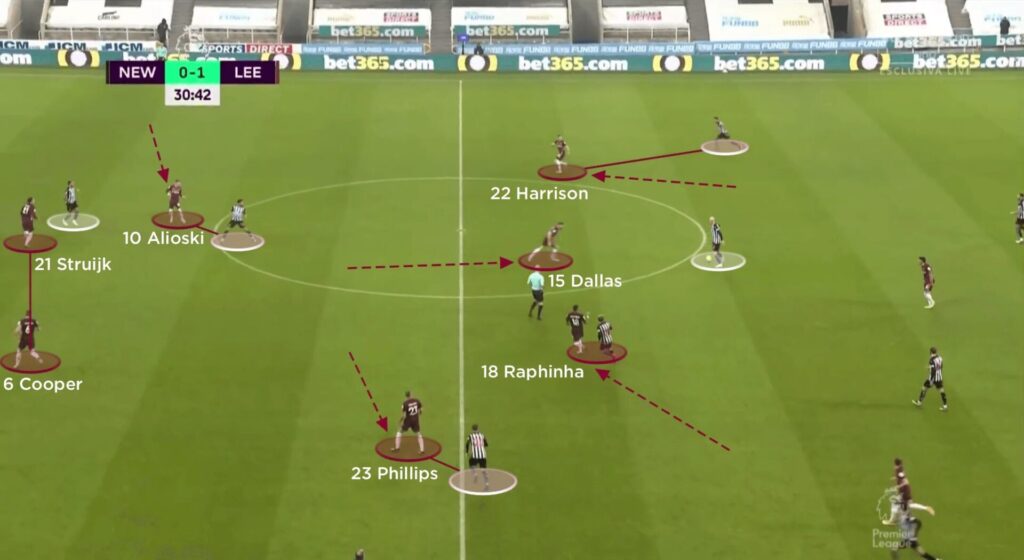

It’s the close-nit-suffocating nature of the man-to-man approach that fits better than the zonal approach. The zonal approach can still be bypassed by players who don’t need that much room to work in, but the man-to-man approach gives them little to no room to work in. It’s goal is to force the players backwards, with their only root forwards at times being a long ball from a centre-half, or a hoof upfield by a goalkeeper. This was one of the reasons Alisson had the most forward passes in the Liverpool team against Atalanta.

Within our Sunday League game, our zonal and passive approach allowed the centre-halves to drive into acres of space due to the fact we had been pushed into a low to mid block. The full-backs pushing forward and the lack of communication and tactical instruction as to who was pressing the centre-halves caused confusion, which allowed them to pin us back and deliver a number of balls into wide areas that caused us countless issues.

Asking our wingers to mark their full-backs at every juncture negates this situation. It allows the centre-forward to put even more pressure on their centre-backs when they are in possession, and it also allows us to possibly commit our number ten into pressing their other centre-back, either forcing the one in possession long or back to the goalkeeper.

Instead, due to our zonal approach, they had acres of room to run into, which took our players out of the game on more than ten occasions per half and resulted in us losing 3-1 despite taking a 1-0 lead into halftime.

Jack Fawcett’s explanation of the man-to-man approach was mesmerising. He started off by describing how the hybrid roles in a zonal approach can be easily bypassed due to the fact that they are easily countered at times by the opposition. This can be done by pushing the full-backs high (which is what cost us our final), because it makes the task of covering that ground virtually impossible unless you have ten outfield Yohan Blake’s. Man-to-man pressing systems are much harder to counter.

If a team does not mind their organisation being disrupted due to the fact that a man-to-man approach may require numerous rotations in the game, it’s a system that’s likely to bear fruit for the team deploying it, if done right, of course. It’s a system that looks to nullify threats and make it difficult for the opposition to build attacks and momentum, which is a trait that, were it to be bottled, could be sold for billions in the football market.

Bielsa Ball:

As previously mentioned, if done correctly, the man-to-man system aims to push the ball back to the goalkeeper, the only spare player on the pitch. He will then be forced more often than not into a long pump up the park, which you would expect your duel winners and aerial general’s to win on the first ball, with your duel winners also expected to win the second ball.

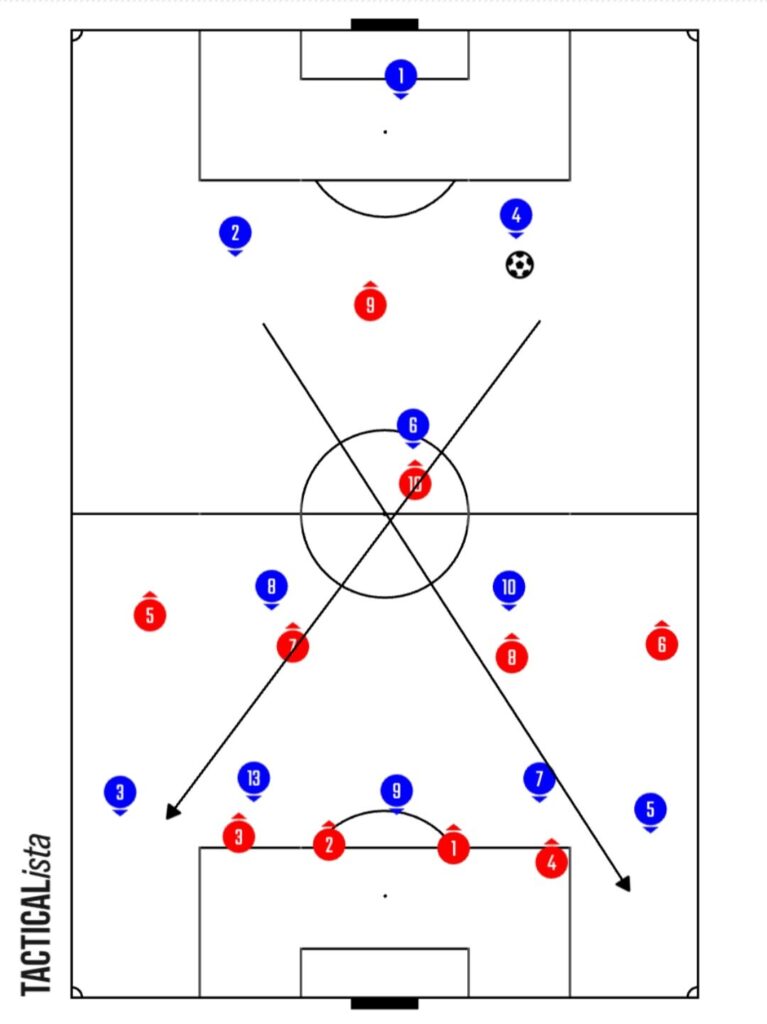

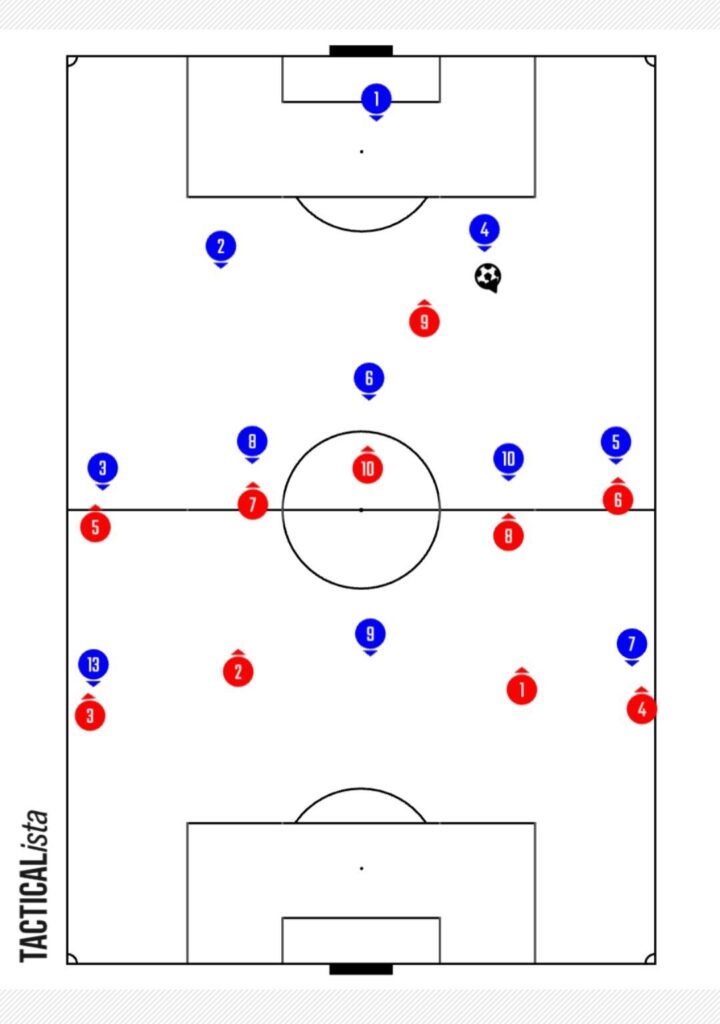

The system isn’t deployed by many in the modern game, but the likes of Gian Piero Gasperini and Marcelo Bielsa are two managers that are closely linked to the art of it. Bielsa has applied the approach at every club he’s been at. Bielsa’s concept is to have a 2v1 in the central defence area, with two defenders against one attacker, provided the team in question is deploying a 4-3-3 or a 4-2-3-1. Not many teams play 4-4-2 these days, so more often than not, this will be the case in the modern game.

Bielsa also likes his teams to have a 3v3 in the middle of the park, with the full-backs marking the wingers and the wingers marking the opposition full-backs. There is a 2v1 against Biela’s teams when pressing, as the striker will be left alone against two defenders in the build-up, but this is where the striker has to be clever in his pressing and try and curve his runs to force the defenders in possession backwards or to play long.

If a team does play two strikers, Bielsa would play a back three and likely go to a 3-4-3 formation all over the park, so the man-marking system does not change. You effectively try to trap the opposition inside their own half and negate their ability to build attacks up the pitch. The striker’s pressing cuts the pitch in half and forces the defender in possession to find passing lanes that may not exist due to the system being deployed all over the park.

The tactic requires every outfield player to aggressively follow the player they’ve been tasked with marking. As previously cited, it does not matter where that player goes on the pitch; you follow him. The most famous example of the man-marking system is Ander Herrera following Eden Hazard around Old Trafford, with many joking that he even followed him home that night. Such was his devotion to achieving the feat of nullifying his threat on that day against Chelsea.

It’s a system that, although not used by every side in modern football, is still one of the most effective in the game today. If my team had deployed it last Friday night, we’d likely be the champions of one of the most prestigious pots in Irish amateur football, but unfortunately, that’s the way the cookie crumbled.

One Comment