Pep Guardiola: The Concept of Adaptability & Ingenuity

“Change is the law of life, and those who look only to the past and present are certain to miss the future.”

– John F. Kennedy

Managers come and go, teams come and go, dynasties come and go, and tactics come and go, but what never goes in football is change. Change is a constant in football; adapt to change and conquer; or be persistent in your ways and remain in a never-ending chasm of defeat.

The best managers and teams are very receptive to change. Pep Guardiola, one of the most decorated managers in world football, is no stranger to change. The reason why he’s still very relevant today and why he continues to influence other coaches is due to the way he constantly adapts to change and evolves as a manager.

As a Cruyff believer and protégé, there are very similar patterns between Pep’s football and Cruyff’s football. The basic idea is to keep the ball all while creating advantages over the opposition by focusing on the positioning and movement of the players to generate superiorities. This is called ‘Juego de posicion’, also called ‘Positional Play’.

However, over the years, Pep has adapted many times and has added some slight tweaks to his system across all the teams he has coached. Though the general principles exist, Guardiola’s City didn’t play the same way his Barcelona team did, and his Barcelona team didn’t play like his Bayern side.

This article sheds light on the various ways Pep has changed and adapted over the years, as well as the differing tactical solutions he provides when his team is stuck due to differing obstacles thrown at them.

Guardiola At Barcelona

Pep Guardiola was appointed as Barcelona head coach on May 8th, 2008, to replace Frank Rijkaard. There were lots of questions asked about how experienced he was to take on such a big job, especially with the fact that his only previous role was coaching Barcelona B. Although he won the 3rd division with that team, questions were still asked about his experience.

Once appointed, he made very quick decisions regarding the players in the squad. He announced that stars such as Ronaldinho, Deco and Eto’o would not be allowed to remain in the team. Although Eto’o remained in Pep’s first season, he left the following season. He then brought in Dani Alves, Pique returned from Manchester United and Busquets and Pedro were promoted to the first-team squad. All important players to the Barcelona dynasty under Pep Guardiola.

At Barcelona, Pep had different tactical innovations and adaptations throughout his tenure.

He brought in more structured possession. Riijkard’s Barcelona were too flamboyant and attacked with a lot of flair, but this led to them being quite open and underwhelming at times. Individual flair was also relied upon more under Rijkaard. Pep sought to change this by making the team more cohesive as a unit. Every pass was calculated, and players held their positions. This was to make sure they were in a good position to counter-press immediately after they lost the ball. The varying formations and structures used would be examined later, but the main defining feature of Pep’s tenure at Barcelona was the introduction of the “false 9,” which exploded Lionel Messi to world-class status.

One of the best things about Guardiola’s managerial style is his ability to create, as well as his innovation, due to his deep understanding of the game. The false 9 is just one of his numerous genius tactical adjustments.

False 9 & Messi

No player was more important to Guardiola’s success at Barcelona than Lionel Messi. Messi started his Barcelona career as a right-winger. Although he was good in that role, he never really attained world-class status until Pep changed his position from a right winger to a false 9.

A false 9 is a centre-forward who repeatedly moves towards the ball in deeper positions from a high starting position. This is done to get away from the opposition centre-backs, draw them out of position to create space for others, as well as combine with the midfielders. This deep movement confuses defenders, as they’re not sure whether to follow the forward into midfield or stay put. If they stay put, the forward combines freely with his midfielders and creates overloads; if they follow, space is created behind them.

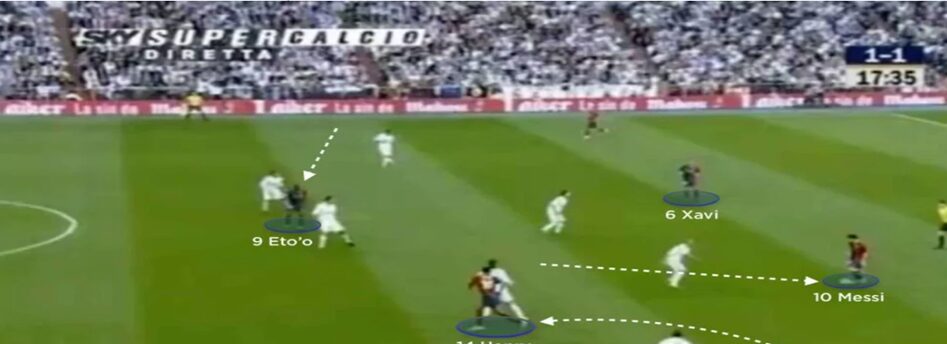

Guardiola unlocked Messi’s true potential by making him a false 9. Pep came up with the idea the night before Barcelona’s title-deciding matchup with Real Madrid in May 2009.

“Pep noticed how much pressure the Madrid midfielders Guti, Gago, and Royston Drenthe put on his players, Xavi and Yaya Toure. He also noticed the tendency of the central defenders, Cannavaro and Metzelder, to hang back near Iker Casillas’ goalmouth. This left a vast expanse of space between them and the Madrid midfielders—a vast, space,” wrote Marti Perarnau in Pep Confidential.

Guardiola decided to unleash Messi in that space as a false 9 after explaining the idea to him the night before the Clasico. The strategy worked perfectly as Barca destroyed Real Madrid, winning by six goals to two. Messi also put up a great performance, scoring twice. Pep Guardiola stuck to the system from that day on. This move by Pep illustrates his ingenious ability to make changes that shift the balance of a game in his team’s favour.

Pep Guardiola’s use of Messi as a false 9 was very thoughtful, as he saw that Messi’s potential would excel in that role rather than him playing on the right wing. Messi had exceptional awareness of his surroundings, coupled with his dribbling, which allowed him to go past multiple players and create space for his teammates on the pitch.

This made him a very important middleman who linked the midfield to the attack; constant interplay with Xavi, Iniesta, and Busquets was very common. Apart from this, Messi had great vision and constantly opened defences with it. He was also a potent finisher; after coming deep to link up play, he made late runs into the box to finish off cutbacks.

The false 9 role Messi played created numerical superiority for Barcelona in the midfield, as he would come deeper to play with Xavi, Iniesta, and Busquets. This meant that Barcelona had four men in the middle against three.

This extra man in midfield helped Xavi and Iniesta have more space and helped Barcelona dominate possession. Barcelona’s success and cohesive, dominant football in Pep’s reign were largely because he had Messi executing a demanding role with ease. This foresight to play Messi as a false 9 is a big reason why Barcelona was very successful under Pep, winning a sextuple in his first season. He won another Champions League in 2011, and 14 trophies in total in his four years as Barcelona boss.

Lionel Messi also had his most productive seasons under Pep, having 305 goal contributions (211 goals and 94 assists) in 219 games per transfermarkt. Messi also won 4 Balon d’Ors under Pep’s tutelage, confirming his status as a world-class player and one of the all-time greats.

Formation & Systemic Changes

During Pep’s reign at Barcelona, he mostly used a 4-3-3 system with an emphasis on ball possession and ball retention. High pressing that aimed to win the ball within 6 seconds was another defining feature.

Although they held most of the possession, it wasn’t just for the sake of it; there were positional, qualitative, and numerical advantages created all over the pitch to score goals. This was called positional play. It was usually mistaken for Tiki Taka but Pep himself hates the term as he feels the description is wrong.

In Pep Confidential, he said, “I loathe all that passing for the sake of it, all that tiki-taka. It’s so much rubbish and has no purpose. You have to pass the ball with a clear intention, to make it into the opposition’s goal. It’s not about passing for the sake of it. Don’t believe what people say. Barca didn’t do tiki-taka! It’s completely made up! Don’t believe a word of it!”

The team was very possession-dominant, and it started with those at the back. Victor Valdes was comfortable with the ball and Barcelona built up from the back with his good ball distribution. Possession was also used as a defensive tool, as the logic was that by having his team control the ball, the opposition had fewer chances to attack. The width was provided by the wingers in Henry, David Villa, and Pedro, while Dani Alves also had a licence to overlap.

Positional play football reached peak levels in 2011 because Barcelona had spent 2 years playing the system. As a result, there was more familiarity with what was required from each player and their roles.

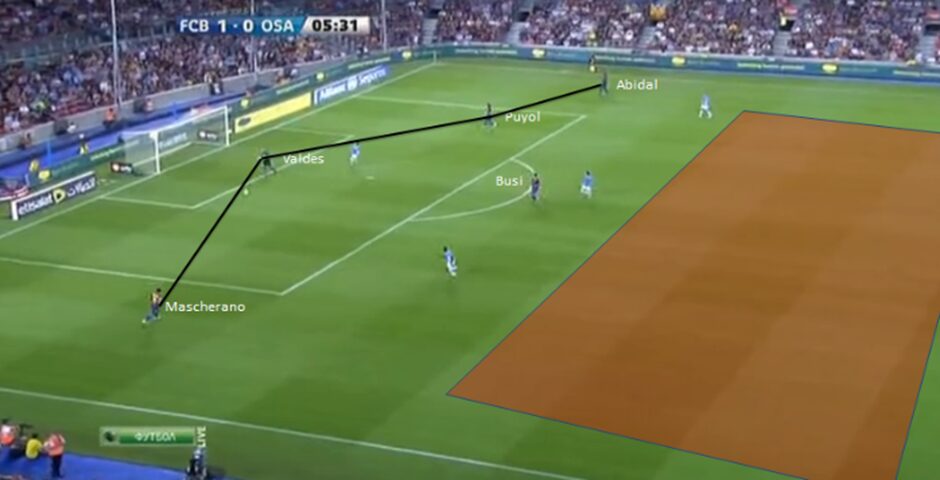

For Guardiola’s Barcelona, there was an emphasis on building up from the back. Victor Valdes, who was an extra man and a ball-dominant goalkeeper, made this possible. During this period, this was a foreign concept, as most goalkeepers usually played long from goal kicks.

The build-up structure outnumbered the opposition’s first line of pressure. If the opponent pressed with one striker, they’d build up with the two centre-backs plus the goalkeeper to make it 1-2. However, if the opponents pressed with two forwards, Sergio Busquets usually dropped in between the two centre-backs, who would have split wide. This would make it a 1-3 buildup shape. The wingers also held their positions high and wide, pinning the opposing fullbacks and making it difficult for them to go forward and back the press.

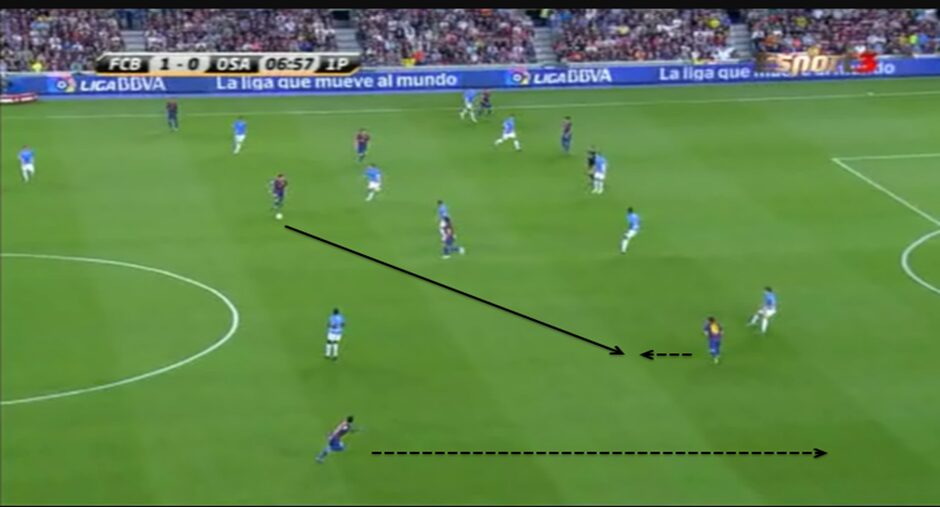

To make things worse for the opponents, Messi would drop deep, joining Xavi and Iniesta in midfield. This ensured numerical superiority in midfield and made Barcelona a difficult team to press.

When the first phase has passed and they’re in the second phase, the players hold their positions, and the wingers stay wide to drag defences horizontally. Barcelona would usually build-up play on one side, dragging opponents across while creating a free man on the flanks. The far-side player would have space to beat his fullback as he’d be 1v1, creating easier scenarios for a cutback or putting a cross into the box for the arriving midfielders and forwards to score.

These tactics led to numerous successes in 2010–11. It was a tough task to beat this successful season and improve the squad even more, but Pep Guardiola took on the challenge and made slight tweaks to his system in the 2011–12 season.

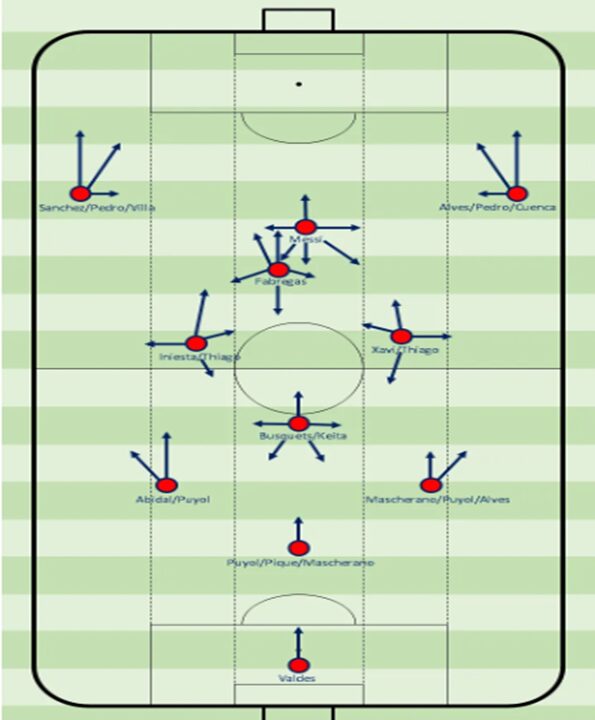

In the following season, Barcelona moved to a more dedicated back three. Instead of the 4-3-3 formation used in previous years, it is now a 3-4-3.

Guardiola had just signed Cesc Fabregas from Arsenal for the sum of €34 million, which was a bargain back then. The challenge now was for Pep to fit him into a team that already had the best midfield (Xavi, Iniesta, and Busquets) at the time. The thinking behind Pep using this structure could come from this quote from a Sky Sports interview with Gary Neville and Jamie Carragher in 2018: “The problem was, we had Busquets, Xavi, Iniesta, Messi, and Cesc [Fabregas] and they were so good. I was thinking all the time about putting them together… I knew when they were all together, we were so good.”

In this new system, Abidal, who was a left-back, would tuck in to become a left-sided centre-back, while Dani Alves, on the other side, would hug the touchline on the right flank, akin to a winger. Depending on who was starting, David Villa, Sanchez, or Pedro provided the width on the left. Fabregas, from the attacking midfield position, roamed with Messi in midfield. It resembled a double-false-9 system. The dropping of both Messi and Fabregas to combine with the Xavi-Iniesta-Busquets midfield improved Barcelona’s passing through the middle even more, made defences come narrower and created space out wide for the wingers to beat their marker 1v1.

Also, compared to the Barcelona team of previous seasons, the 11/12 iteration had more positional fluidity and the players had a lot of freedom, which made this team unique. Although this team didn’t win the league, they won the Copa Del Rey.

Pep Guardiola left the team after this season, claiming he felt exhausted. His legacy would never be forgotten, as he’s the youngest manager to win the Champions League, as well as being the manager who won Barcelona’s first treble. He took a year off football to recharge.

Guardiola At Bayern Munich

After a yearlong sabbatical, Pep decided to come back into management. Bayern Munich announced in January 2013 that he would succeed Jupp Heynckes at the end of the 2012–13 season. When this announcement was made, the football world took notice of Bayern’s intent. The anticipation grew after Bayern won the treble in 12/13. “How better would this Bayern team get?” and “How would Pep improve this team further?” were the questions on everyone’s mind.

“I’m ready… My time at Barcelona was wonderful but I needed a new challenge. Bayern gave me that opportunity.”

– Pep Guardiola

Pep Guardiola was insistent on signing Thiago Alcantara from Barcelona upon his arrival in Munich; this signalled a change in Bayern’s style under him from Heynckes’ containment and counterattack-based strategy to a more possession-heavy style. In his first press conference as Bayern coach in 2013, Pep admitted, via Bleacher Report, “that he would have to evolve his tactical approach away from that which made him a success at Camp Nou: “Barcelona players have different qualities to those of Bayern. I need to adjust.”

Due to the Bayern team being different to his Barcelona sides, there were various changes made to the team in terms of their overall play. Although he laid down his blueprint on this Bayern side (positional play, high pressing and counter-pressing), there were slight tweaks due to personnel.

For one, there was more emphasis on wing play to emphasise the lethal power of Arjen Robben and Franck Ribery. It was impossible to recreate the Messi magic at False 9 in Bayern Munich; thus, setting up the wingers with 1v1s against their fullbacks was a priority. This is a major reason why Pep signed Douglas Costa and Kingsley Coman, two young, dynamic wingers who love to put defenders on the back foot. A major tactical theme he introduced at Bayern was the use of inverted fullbacks.

Inverted Fullbacks

Traditionally, fullbacks are known to overlap their wingers and provide support outside of them. However, fullbacks who move into central spaces when their team has the ball are known as ‘inverted fullbacks.’ The reasoning for this is twofold. First, they provide an extra presence in the centre of the pitch to overload the opposition in midfield. Also, in defensive transition, they help provide cover in central spaces after the ball is lost. Inverted fullbacks should have positional awareness as well as the vision and technical ability to play in the middle of a pitch that is usually congested.

When Pep came to Germany, he noticed that the teams were so dangerous in transitions and that if he allowed the fullbacks to overlap, they would be exposed to counterattacks. Also, to utilise the dribbling ability of his wingers, inverting the fullbacks meant that they had more space for 1v1s.

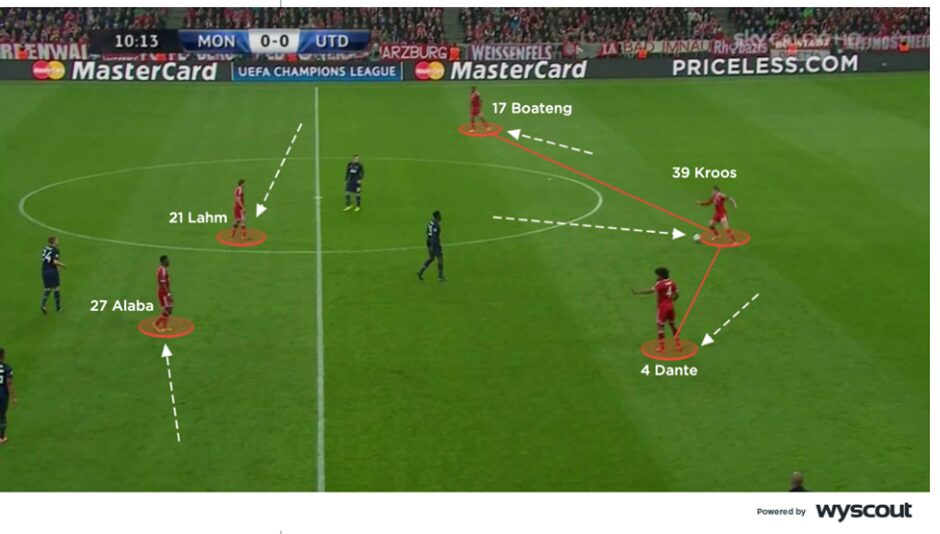

Guardiola used Philip Lahm and David Alaba as inverted fullbacks who would move inside when in possession. Their ability to receive under pressure and create passing angles made them very effective in this position. It also protected Bayern from counterattacks better, as by inverting into midfield, the team was more prepared to lose the ball.

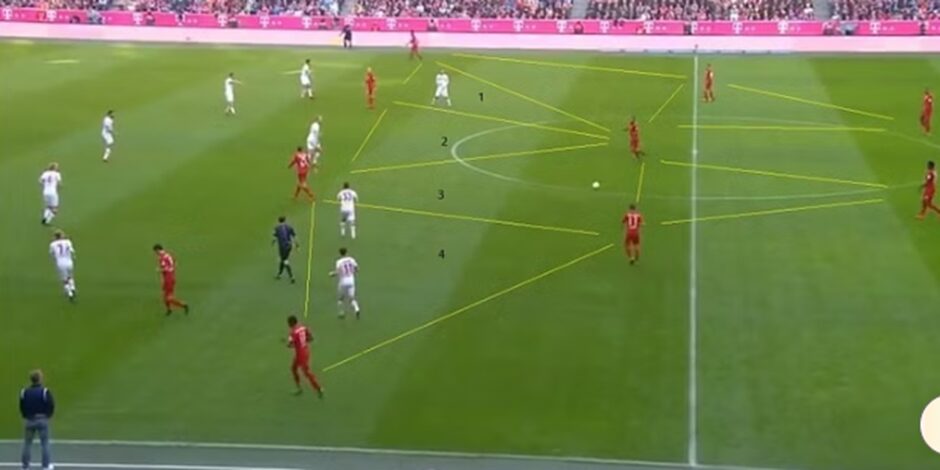

Having more numbers in the middle also meant that there was more space for their wingers to work with. Opposition teams will typically try to counteract the quantitative superiority in the middle by instructing their wingers to come infield to even things up. However, this in turn creates a one-on-one scenario between the winger and the opposition’s isolated full-back. This created ideal situations for Ribery, Robben, Costa and Coman.

Because at Bayern there were more traditional number 9s and box finishers like Lewandowski, Mandzukic, and Muller, it only made sense for him to prioritise wing attacks to fashion chances for the forwards. This led to Lewandowski leading the Bundesliga scoring charts in 15/16 with 30 goals. Muller, Ribery, Robben, and Costa also had very productive seasons under Pep Guardiola.

Robert Lewandowski was brought in, not only to apply the finishing touches to team moves but to also help the team build up.

High Line & Pressing

Pep Guardiola also brought his high line and high pressing to Bavaria. This coincided with their high tendency to keep possession. Pep’s team aimed to make the pitch as small as possible when they didn’t have the ball. By having a high starting defensive line, there was less space in between the lines for the opponents. However, there was space in behind the defence. This was a risk Pep was willing to take because he had Manuel Neuer, a ridiculously good sweeper-keeper who had good awareness of his surroundings. Neuer revolutionised the sweeper-keeper role, as he was comfortable defending large spaces.

Due to Bayern’s dominant style of play, Neuer can sometimes be spotted camped high up the pitch, near the halfway line. He is also very good with his feet as well as his hands. His rocket of an arm allows him to set counterattacks up quickly.

Guardiola’s arrival at Bayern Munich in 2013 made Neuer even more aggressive in his sweeper-keeper duties by moving the defensive line from an average of 36m to 43.5m away from their own goal.

Another tactical evolution Pep brought to Bayern was the 2-3-5 formation in the latter parts of his Bayern reign. In the 2015/16 campaign, this was seen more often, and it was effective in the league against teams that defended and waited for the counterattacks.

By having 3 players in front of the back 2, a safety net was provided against transitions, and a base for ball circulation was also formed. The two wingers maintain width by staying high and wide all the time to stretch opposing defences. It was also their responsibility to beat their man and cross it for Lewandowski, the advanced midfielders, and the other winger to latch on to. If the situation wasn’t ideal, then the ball would quickly be circulated to the other flank, where the other winger is handed the same task.

Although Pep Guardiola at Bayern couldn’t win the Champions League, he won the league every year he was there while setting new records.

Guardiola’s Bayern scored 254 goals in 102 league matches—a Bundesliga record—and they conceded just 58 goals in total, at an average of 0.6 per game. He combined a ruthless attack with a mean defence, with no coach who has taken charge of more than two league games boasting a better defensive record, which includes 59 clean sheets. He won 82 out of 104 games, a win percentage of 80.4, which destroyed that of his closest challenger, Ottmar Hitzfeld (58.4%). He also won the Bundesliga in record time, after 27 games in 2013/14.

He left the club after 3 successful seasons, and he is known for changing the way Bayern played football with various tactical innovations as he continues to be in a constant battle with himself to achieve perfection.

Guardiola At Manchester City

February 12, 2016, was the day Pep signed with Manchester City ahead of the 2016–17 season. There was huge hype surrounding the move, as England was welcoming one of the most revered tacticians of all time. Apart from this, there was an eagerness to see whether Pep’s possession football would work in the Premier League.

When Pep arrived in England as City coach, the path to creating his blueprint began. He brought in Ilkay Gundogan from Borussia Dortmund, Leroy Sane from Schalke 04, John Stones from Everton, as well as Claudio Bravo from Barcelona and Nolito from Celta Vigo.

Due to Pep wanting to introduce his possession style, he needed a goalkeeper capable of playing out from the back. He ruthlessly let go of John Hart and replaced him with Bravo, which didn’t go well with City fans because he was a legend and served the club for many years.

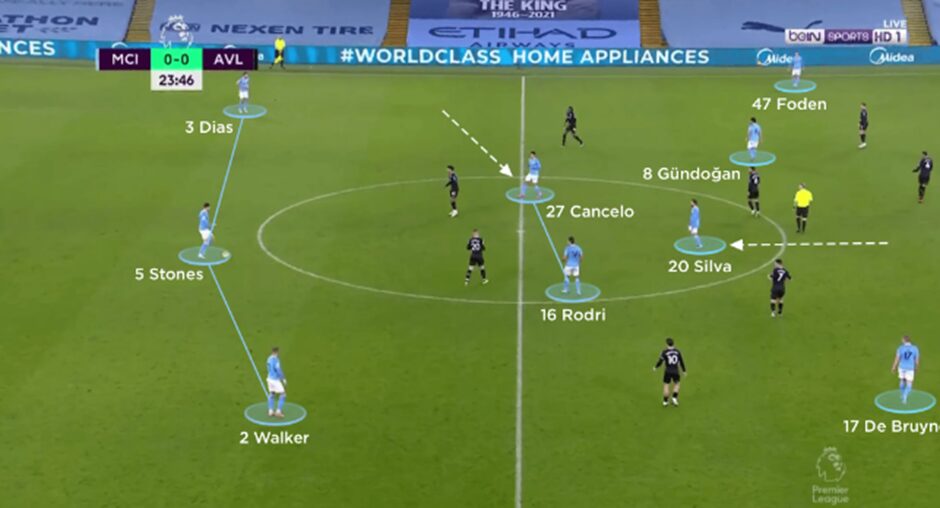

His first season at Manchester City saw him bring the inverted fullback system with him while dropping his defensive midfielder into central defence when playing out from the back. At the time, this was a first in the Premier League. That strategy helped to push his attacking midfielders higher and slightly wider, where they took up positions in the half-spaces.

However, the fullbacks were not up for the task due to their ageing as well as their lack of the required skills needed to play the role.

Apart from this, Pep’s insistence to play out from the back and press very high saw his team being punished more often, and Bravo had a disaster of a season. Due to the old age of the inverted fullbacks (Kolarov, Clichy, Sagna, and Zabaleta), they did a poor job protecting the middle of the pitch, and this led to Manchester City conceding many goals from transition and some embarrassing defeats, such as the 4-0 defeat to Everton, which was Guardiola’s largest ever domestic defeat.

Although his philosophy was clear, the problem was the defence, as well as the squad not being in his image since he was forced to play with so many of his predecessor’s squad. Guardiola, for the first time in his glittering managerial career, ended the 16/17 trophyless season. City exited the Champions League at the last 16 stage, finished third in the Premier League, 15 points behind champions Chelsea and failed to win the EFL Cup or FA Cup.

Ahead of the 2017/18 season, Pep gave reasons why his first season in English football was a struggle. He stated: “Last season, I played with eight or nine players in the Premier League who were bought by Manuel Pellegrini. They’re good players, but you have to rejuvenate the team. It was a team that was very successful, but it had outgrown itself. It was one of the oldest teams in the Premier League.”

Even though critics maintained that Pep’s style wouldn’t work in England, Guardiola ahead of pre-season 2017 vowed that City would perform better with more of his signings and the team having a year to understand his philosophy.

In the 2017 summer transfer window, Pep needed to change his fullbacks due to them being a major hindrance to implementing his tactics. There was also the need to buy a new goalkeeper, as Bravo had a disaster of a season. He brought in Kyle Walker from Spurs for £45,000,000, Benjamin Mendy from AS Monaco for £49,300,000, and Danilo for £26,500,000. He also added Ederson and Bernardo Silva from Benfica and Monaco, respectively.

Inverted Fullbacks, Free 8’s, & Wide Wingers

The arrival of Walker, Mendy, and Danilo allowed Man City to use the inverted fullbacks much better than Pep’s initial season. It meant that their defending against transitions was better since they had the legs and quickness to cover ground compared to the fullbacks they had the previous season. It also allowed Manchester City to play their high line with more confidence, improving their defence and conceding fewer goals. Walker and Mendy would come inside to provide passing options for the defenders, as well as mitigating counterattacks in a 2-3 or 3-2 structure, depending on how many attackers the opposition kept.

When Mendy got injured, Pep had no traditional left back in the team, but his ingenuity led to Fabian Delph coming in to play the role as he was more of a traditional midfielder, and as a result, he slotted in effortlessly.

This gave more space to Kevin De Bruyne and David Silva, who could now attack better with confidence. They worked in tandem as playmakers, operating in the two half-spaces to combine with their respective wingers, who held their width. Pep thought that instead of having only one playmaker, if he had David Silva and Kevin De Bruyne in advanced positions, they could cause a lot of damage. Pep made them more advanced than ever.

They weaved between opposition lines, floating between the 8 and 10 positions. Kevin De Bruyne gave the role its name. “It’s a different role,” De Bruyne told the Belgian newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws. “It’s all right. It’s a little change but it’s all right. The coach has his tactics. I play not as a No. 10 but as a free eight with a lot of movement everywhere.”

Due to the wingers (Sane and Sterling) staying wide, they created space in the middle of the pitch for the attacking midfielders. Thus, City used five men across the pitch in attack: Sane and Sterling holding the width, De Bruyne and David Silva in the right and left half spaces, respectively, and Aguero in the middle.

City essentially used a 2-3-5 shape or 3-2-5 in possession for most of the 2017/18 season and won the league in record fashion, having the most points ever in a season history with 100. The same continued in 2018-19, where they won the league with 98 points, winning every single game in the league from January 2019 to May 2019, slightly edging Liverpool’s 97 points in arguably the most intriguing title race in history.

False 9s & Double False 9s

With Aguero’s injury problems mounting in 2020 and 2021, where he missed a combined 45 games due to seven injuries, Pep had to come up with a plan to keep City competitive in front of goal. One of the most fascinating things about Guardiola is his ability to conjure solutions when things aren’t going well. Gundogan revealed Pep’s desire to play a game of football with 11 midfielders in the Players’ Tribune, saying, “He once told me, “I wish that I could play with 11 midfielders. You guys can all see the game five steps ahead.”

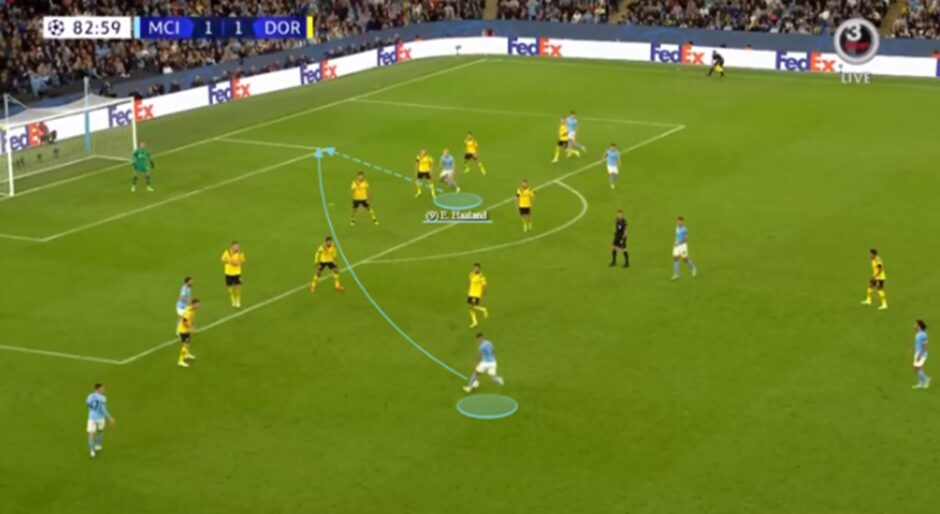

The choice not to play classic strikers is one of the oldest strategies of his career and the even more radical choice of playing two ‘false nines’ had already been tried with Manchester City during the UEFA Champions League round-of-16 match against Zidane’s Real Madrid in 2020. During that game, Bernardo Silva and De Bruyne started from central positions and then dropped deep, occupying Casemiro. When this happened, the wingers no longer stuck to the touchline as religiously as in previous seasons; instead, they attacked the spaces created by the false 9s.

At Barcelona, the false 9 was inevitably Lionel Messi, but at City, Pep surprised opponents since different City players could play that role. Riyad Mahrez, Phil Foden, Bernardo Silva, Kevin De Bruyne, Ilkay Gundogan and even wingers such as Raheem Sterling and Ferran Torres have played the role. So, there was an element of surprise.

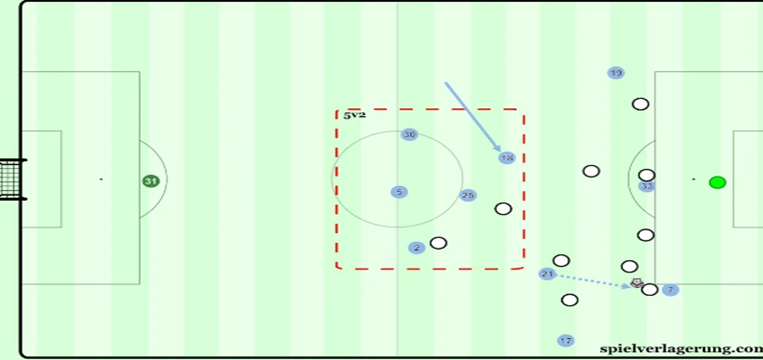

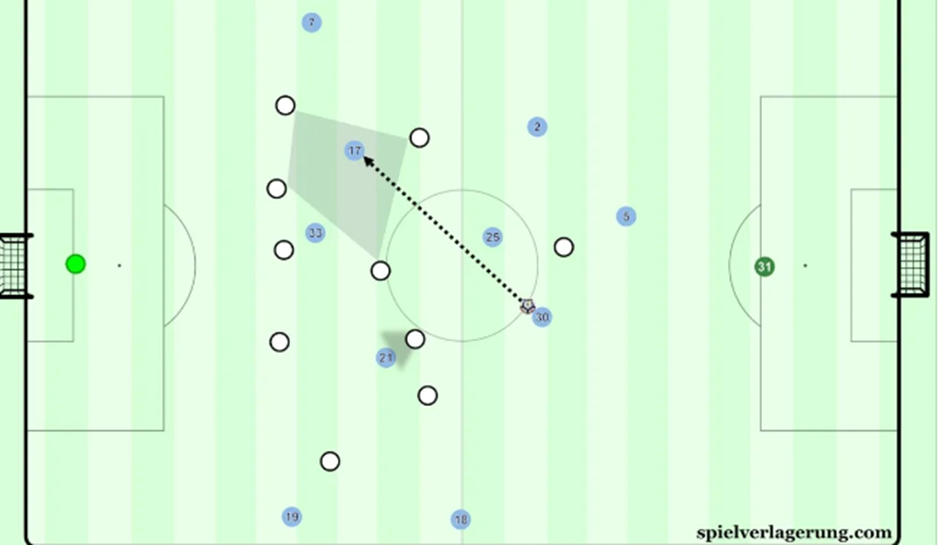

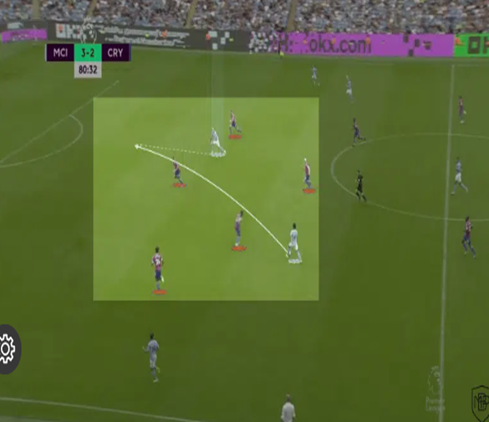

With the use of the double false 9 system, more space was created dynamically. Starting from their internal positions, De Bruyne and Bernardo Silva try to move according to the defenders’ behaviour to overload a certain area or lure an opponent out of position to have more space to attack behind the defensive line or to create isolation on the weak side. They also link with other teammates, trying to support the build-up.

Whenever any of the False 9s vacate the middle and drift wide, other players invade the middle. The positioning of the double false 9s created a lot of confusion for the opposition, and one player who benefitted from the space created was Gundogan. The German had the most prolific goal-scoring season of his career and had the most chances of freeing himself in the final third. Sometimes, both false 9s could drift into the same flank, overloading and outnumbering the opposition, creating space on the other flank for a far-side winger or fullback to attack.

Bernardo, De Bruyne, Foden, and Gundogan are all versatile players who are good progressors of the ball as well as playing in tight spaces. All can receive the ball on the half turn, and this is why the false 9 system worked. Manchester City used this tactic in the 2021 and 2122 seasons and won the premier league. A remarkable feat is that the team scored 99 goals in the league in 21/22, playing without a focal point for the entirety of the season as Aguero left the club.

Pep made a crucial change that showed his adaptability to demanding situations.

Haaland & Stones’ New Role

The Champions League had eluded Pep since he left Barcelona in 2012, and his critics kept beating him with the ‘Pep is useless without Messi’ stick. The closest he came to winning the UCL was in the 2021 final against Chelsea, where they were beaten 1-0.

After losing Aguero and Jesus during the previous years and playing the last two seasons without a recognised number 9, Manchester City in the 2022 transfer window purchased Erling Haaland. He was the hottest striker in high demand at Borussia Dortmund and he came for a fee in the region of £52 million. Manchester City beat Real Madrid and Bayern Munich in the race for Norway.

This was a very exciting transfer because the football world wanted to see how Haaland would improve his game much further. Apart from this, it was interesting to see how Pep would adapt his tactics and build around the traditional number 9, having used a striker-less system in the past two seasons.

The first noticeable change in the 2022–23 season was that Pep’s side now consistently had a threat inside the box. This led to the city putting in more variety of crosses from out wide. Previously, Manchester City used low cutbacks most of the time after working the ball down the flanks due to the lack of height in the centre; now, they can cross the ball with more height. Haaland had incredible movement inside the box, and this allowed him to be in the right place at each moment. His movement in the box, combined with his strength and lethal finishing, made him a very difficult opponent to mark for most defensive setups.

The addition of Haaland also gave City more ways to attack the opponent. Apart from the variety of crosses that City could now play, he allowed Pep to adopt a more direct approach than you would associate with his teams. From goal kicks, if the opposition is pressing and their defensive line is very high, Ederson could play the ball directly to Haaland, who would hold it up and combine with a nearby midfielder, usually Kevin De Bruyne. We saw this approach work against Arsenal and Bayern Munich. Previously, City weren’t this direct because they lacked a powerful forward, so they played through the thirds more and were more dangerous from counterattacks than ever before.

Apart from this, Haaland also gave City the option of playing balls in behind when they had the opportunity due to his pace. His strength also meant that anyone involved in a foot race with him would most likely lose. This made defences reluctant to push their defensive line higher up the pitch.

Haaland seemed impossible to stop, so throughout the season, teams started to man-mark him, sometimes even using two defenders. Pep recognised this and made Haaland a decoy for others to have more space. Haaland had gravitational pull in the sense that he dragged multiple defenders away from their positions, which created more space for the midfielders to vacate into. There’s no doubt that Pep adapted well to Haaland, as he had more ways of playing. Under Guardiola’s tutelage, in his first season, Haaland scored 52 goals in 53 games in all competitions. He also scored 36 goals in the Premier League, the most ever scored in a season, as well as breaking numerous other records.

During the 2022–23 season, Pep had to make a very important tactical change to keep the team fresh.

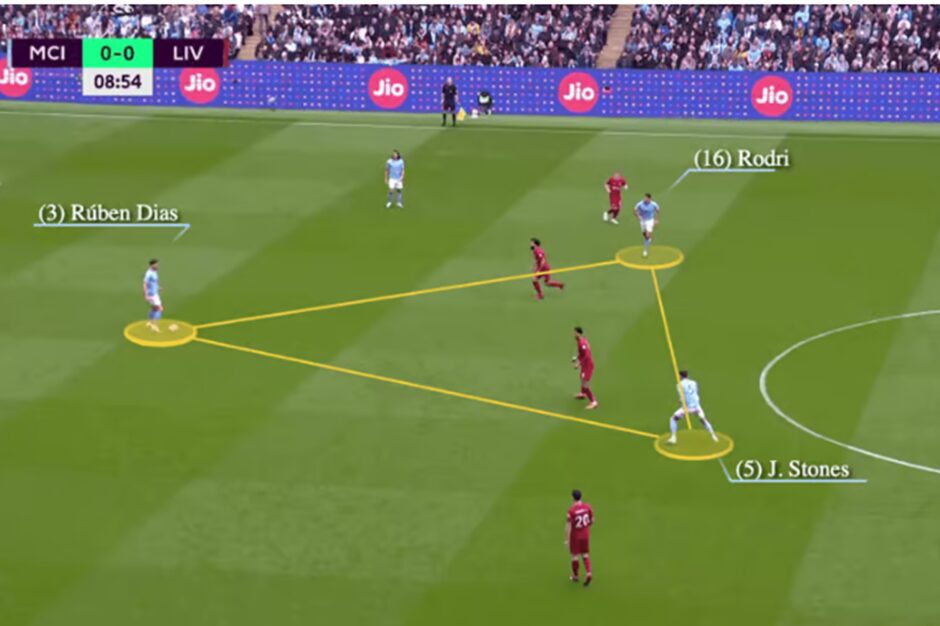

He started using John Stones in a hybrid midfield-defence role to assist Rodri in the middle of the pitch and provide an extra defensive body without compromising the midfield progression. Stones’ role might be one of Guardiola’s greatest tactical tweaks, as it played a crucial role in the club’s best-ever season in history.

Without the ball, John Stones went to the defence, sometimes even as a right back. With the ball, Stones formed part of the new midfield diamond (KDB, Rodri, Gundogan, Stones) and often ventured into the attacking third. The reason for the box midfield was to outnumber the opposition midfield. Since the departure of João Cancelo to Bayern Munich and after a spell of using Rico Lewis as an inverted full-back in possession, which worked well in fairness, Guardiola seems committed to lining up with four nominal centre-backs, with Stones playing in the double pivot for most of the game alongside Rodri. A roaming centre-back is very hard to mark because most teams man-mark players in the midfield.

A player who starts at the centre of the backline isn’t usually followed across the pitch, and this helps give City an extra player in every phase of possession. This was seen in full effect against Real Madrid in the first leg, as Madrid went man-to-man across the pitch. Even the midfielders were marked, so Stones usually found himself in space.

When Stones got the ball in space, this disrupted Madrid’s marking scheme, as a Madrid midfielder would attempt to mark Stones, leaving another City midfielder free. Stones’ security with and without the ball at the base of the midfield helps free up Manchester City’s advanced midfielders more, with De Bruyne and Gündoğan playing freer, more advanced roles than ever. Apart from this, he also provides more security when City loses the ball.

Since Haaland meant City could be more direct, this also meant that they were more open to more turnovers and transitions; thus, using Stones provided an extra defensive body out of possession. As exotic as pushing a centre-back into midfield sounds, Stones starts with three other centre-backs beside or behind him. When City loses the ball, they have three centre-backs and at least one of Stones and Rodri behind the ball, ready to snuff out any potential counterattack.

While Haaland would get most of the plaudits for scoring goals, the Stones’ role was a pragmatic tactical adaptation by Pep that gave City an extra player in possession, allowing them to attack better without worrying too much about losing the ball. This change during the season gave City the final push to win a historic treble, including the coveted Champions League.

The series of tactical tweaks and constant adaptations by Pep Guardiola to give his team an upper edge, as well as to keep things fresh, is a major reason for his dominance in leagues and world football in general. The desire for perfection, although it has backfired with some risky decisions, is what makes Pep a revered coach. City is due for more success under him over the years.

One Comment